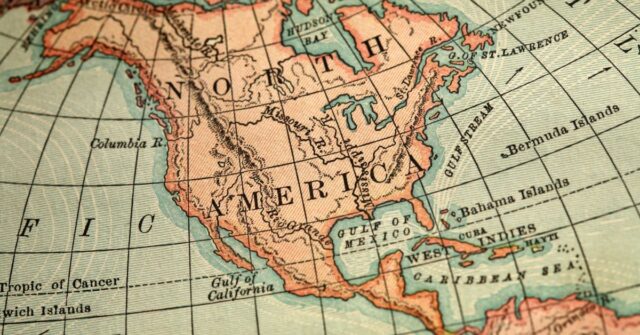

The Viking Age, spanning from the late 8th to the early 11th century, was a time of remarkable exploration and expansion for the Norse people.

Known for their seafaring skills, the Vikings ventured far from their Scandinavian homelands, establishing settlements and leaving a lasting impact on many regions.

Through a combination of archaeological evidence, historical records, and sagas, we will uncover the rich history of these Norse ventures into the North Atlantic.

Read on to gain a thorough understanding of the Viking legacy in Iceland and Greenland.

Discovery and Settlement of Iceland

The Vikings were known for their seafaring prowess, and their exploration led them to the shores of Iceland.

The discovery and settlement of Iceland were significant milestones in Viking history, marking the beginning of their westward expansion.

Early Explorers: Naddod and Floki Vilgerdarson

The discovery of Iceland is credited to Norwegian sailor Naddod, who accidentally stumbled upon the island around 861 CE after being blown off course while sailing to the Faroe Islands.

He named it “Snowland” due to the snowy landscape he encountered. Six years later, Floki Vilgerdarson set out to explore this new land and gave it its current name, “Iceland,” after witnessing icebergs in the surrounding waters.

Despite these early encounters, it wasn’t until 874 CE that permanent settlement began, spearheaded by Ingolfur Arnarson.

His successful establishment paved the way for other Norse families who seeked new opportunities away from the increasingly centralized power in Norway.

Ingolfur Arnarson: The First Permanent Settler

Ingolfur Arnarson, considered the first permanent settler of Iceland, arrived with his family and followers around 874 CE. He chose the site of present-day Reykjavik for his homestead, naming it “Cove of Smoke” due to the steam rising from nearby hot springs.

His successful establishment encouraged other Norse families to follow suit, leading to a wave of migration from Norway, Scotland, and Ireland.

The early settlers were drawn by the promise of arable land and opportunities to escape the growing power of Norwegian kings.

Over the next few decades, hundreds of families arrived, carving out farms and communities along the coasts and lowlands of Iceland.

Archaeological Evidence of Early Settlements

Archaeological excavations have provided significant insights into the early Viking settlements in Iceland.

Findings reveal that these settlers built turf houses and longhouses, structures well-suited to the harsh Icelandic climate.

Sites like the ruins of a longhouse in Reykjavik, dating back to around 871 CE, and other farmsteads across the island, align with the descriptions found in Norse sagas.

These excavations also highlight the settlers’ adaptation to their new environment, from their farming techniques to their domestic life, providing a vivid picture of Viking life in Iceland.

The Role of the Landnámabók

The Landnámabók, or “Book of Settlements,” is a crucial source for understanding the Viking settlement of Iceland.

Compiled in the 12th century, it documents the land acquisitions and transactions of around 400 principal settlers.

This invaluable text not only offers historical records but also provides insights into the social and legal structures of early Icelandic society.

While some details in the Landnámabók may be embellished or mythologized, it remains a vital tool for historians and archaeologists studying the early Norse presence in Iceland.

Challenges and Adaptations in Iceland

Settling in Iceland presented numerous challenges for the Norse settlers. The island’s harsh climate and volcanic landscape required significant adaptation.

The settlers developed innovative farming techniques, such as using turf for building materials and focusing on livestock that could survive the cold winters.

Additionally, they had to import essential items like timber and iron, which were scarce in Iceland.

Trade networks with other Norse territories, such as Norway and the British Isles, were crucial for their survival and development.

Icelandic Society and Governance

Icelandic society during the Viking Age was unique in its governance and social structure.

The establishment of the Althing, one of the world’s oldest parliaments, highlights the innovative approaches to law and order that characterized this society.

The Althing: The World’s Oldest Parliament

The Althing, established around 930 CE, is recognized as the world’s oldest parliamentary institution.

It served as a national assembly where chieftains, known as Godar, met to legislate, adjudicate disputes, and uphold social order.

The Althing was held annually at Thingvellir, a site chosen for its natural amphitheater-like setting.

This assembly played a crucial role in maintaining Icelandic society’s cohesion, allowing for collective decision-making and conflict resolution without a central monarchy.

Social Structure and the Role of Chieftains

Icelandic society during the Viking Age was organized around a system of chieftaincies. Each chieftain, or godi, held both secular and religious authority within their district.

This system, described as an oligarchy, relied on the chieftains to maintain law and order, as well as to lead their communities in times of conflict or hardship.

The godar were responsible for upholding the law, leading religious ceremonies, and representing their followers at the Althing.

This decentralized system allowed for a high degree of local autonomy while ensuring that overarching laws and customs were respected.

Legal System: Laws, Justice, and Blood Feuds

The Icelandic legal system was based on a combination of Norse customs and the laws established by the Althing.

Laws were initially communicated orally and later written down around 1117 CE. The law-speaker, elected for a three-year term, played a central role in reciting and interpreting these laws.

Justice in Iceland was primarily enforced through fines and compensation rather than corporal punishment or imprisonment.

Blood feuds, a common practice in Norse society, were gradually replaced by legal settlements and fines, reflecting a shift towards a more regulated and peaceful society.

Christianization of Iceland

The conversion of Iceland to Christianity was a complex and gradual process.

The arrival of Christian missionaries and the subsequent adoption of the new faith brought about significant changes in Icelandic society, influencing everything from laws to cultural practices.

Early Missionaries and Their Struggles

The Christianization of Iceland began in the late 10th century, with the first missionaries facing significant resistance from the pagan population.

Early attempts by missionaries like Thorvald the Far-Traveler and Stefnir were met with hostility, leading to their eventual expulsion from the island.

The turning point came with the intervention of King Olaf Tryggvason of Norway, who sent more determined missionaries and exerted pressure on Icelandic chieftains to convert.

This external influence played a crucial role in the eventual Christianization of Iceland.

The Conversion Process and Its Impact

The conversion to Christianity was formalized at the Althing in the year 1000 CE, following a period of intense debate and negotiation.

The lawgiver, Thorgeir Ljosvetningagodi, proposed a compromise where all Icelanders would be baptized and publicly adopt Christianity, while still allowing private practice of pagan rituals.

This pragmatic approach helped to maintain social harmony and prevent potential conflicts between the Christian and pagan factions.

Over time, the influence of Christianity grew, leading to the construction of churches and the establishment of a formal ecclesiastical structure.

Compromise and Coexistence of Paganism and Christianity

The initial coexistence of Christianity and paganism in Iceland is a testament to the flexibility and pragmatism of Icelandic society.

This period of dual faith allowed for a smoother transition and reduced the likelihood of violent conflicts.

Pagan temples were gradually replaced by churches, and Christian practices slowly became more integrated into everyday life.

The shift to Christianity also brought about changes in burial practices, legal structures, and cultural traditions, reflecting the broader influence of the new religion on Icelandic society.

Discovery and Settlement of Greenland

Following their successful colonization of Iceland, the Vikings turned their attention to Greenland.

The discovery and settlement of Greenland were driven by a combination of exploration and the search for new resources and opportunities.

Erik the Red’s Exploration and Naming of Greenland

Erik the Red, an adventurous and often contentious figure, discovered Greenland during his exile from Iceland around 982 CE.

After exploring the southwest coast, he returned to Iceland, promoting Greenland as a land of opportunity.

His positive descriptions, likely exaggerated to attract settlers, led to the establishment of two main settlements: the Eastern and Western Settlements.

Erik’s efforts were successful, and by 985 CE, several Norse families had joined him in Greenland, beginning a new chapter in Viking exploration and settlement.

Establishment of the Eastern and Western Settlements

The Eastern Settlement, located near modern-day Qassiarsuk, and the Western Settlement, near Nuuk, became the primary centers of Norse life in Greenland.

These communities were based on farming, hunting, and trading, with settlers raising livestock and cultivating limited crops in the challenging climate.

Despite the harsh conditions, the settlers adapted by relying on resources like walrus ivory, which was highly valued in Europe, and by maintaining trade links with Iceland and Norway.

Farming and Trade in a Harsh Environment

Farming in Greenland was far from easy. The short growing seasons and limited arable land meant that settlers had to be resourceful.

They focused on raising hardy livestock, such as sheep and goats, and supplemented their diet with fishing and hunting.

Trade was vital for the Greenland settlements’ survival. The Norse exported items like walrus ivory, furs and wool, in exchange for timber, iron, and whale blubber.

These exports were crucial for obtaining essential items like timber, grain, and iron from Europe.

The harsh environment necessitated a high degree of self-sufficiency, with settlers adapting their farming and hunting practices to survive.

Environmental Challenges and Adaptations

The Greenlandic climate posed significant challenges for the Norse settlers. Harsh winters, short growing seasons, and limited arable land required innovative solutions.

Settlers built their homes using a combination of stone, turf, and wood, making use of the materials available to them.

Livestock management was crucial. Settlers focused on raising sheep, goats, and cattle, and supplemented their diets with hunting and fishing.

The ability to adapt to these environmental challenges was key to the survival and longevity of the Greenlandic settlements.

Society and Culture in Greenland

Greenlandic society, much like its Icelandic counterpart, was shaped by the harsh environment and the settlers’ resilience.

The Norse in Greenland established a way of life that balanced farming, hunting, and trading, adapting their practices to the unique challenges of the region.

Social Structure and Governance

Greenlandic society was similar to that of Iceland, with a decentralized governance structure based on chieftaincies.

The Norse settlers in Greenland maintained close ties with their Icelandic and Norwegian counterparts, both culturally and politically.

Chieftains, or local leaders, played a crucial role in maintaining order and overseeing trade and agriculture.

The Norse in Greenland also had a communal approach to decision-making, with local assemblies, similar to Iceland’s Althing, serving as forums for resolving disputes and making collective decisions.

These assemblies helped to sustain social cohesion in the isolated and challenging environment of Greenland.

Christian Influence and Church Establishments

Christianity quickly took root in Greenland following its establishment. The first settlers brought their Christian faith with them, building churches and establishing parishes.

The most significant religious site was the bishop’s seat at Gardar, where a cathedral was constructed.

Churches played a central role in Greenlandic society, not only as places of worship but also as centers for community gatherings and social support.

The Christian faith helped to unify the settlers and provided a framework for social and moral conduct.

Interaction with the Dorset and Thule Cultures

The Norse settlers in Greenland were not the only inhabitants of the region. They encountered indigenous peoples, including the Dorset and later the Thule cultures.

These interactions varied from trade to conflict. The Thule people, ancestors of the modern Inuit, arrived in Greenland around 1200 CE, and their presence had a significant impact on the region.

The Norse engaged in trade with these indigenous groups, exchanging goods like metal tools for furs and other local resources.

These interactions highlight the diverse and interconnected nature of Greenlandic society during the Viking Age.

Decline and Abandonment of Greenlandic Settlements

The decline of the Norse settlements in Greenland remains a topic of considerable interest and debate among historians.

Various factors, including climatic changes and environmental degradation, contributed to the eventual abandonment of these once-thriving communities.

Traditional Theories: The Little Ice Age

The decline of the Norse settlements in Greenland has long been attributed to the onset of the Little Ice Age, a period of cooling that began in the 14th century.

This climatic shift made farming increasingly difficult, leading to food shortages and economic hardship. The colder temperatures also impacted the settlers’ ability to trade, as sea ice made navigation hazardous.

However, recent research challenges this view, suggesting that other factors, such as drought and environmental degradation, may have played a more significant role in the decline of the settlements.

Recent Research: Drought and Environmental Degradation

New studies indicate that prolonged drought conditions and environmental mismanagement significantly contributed to the decline of the Greenlandic Norse.

Soil samples and climate data suggest that while temperatures remained relatively stable, decreasing precipitation led to reduced agricultural productivity and pasture quality.

Overgrazing and deforestation further exacerbated these issues, leading to soil erosion and loss of arable land.

These environmental challenges, combined with economic isolation and declining trade, likely played a crucial role in the eventual abandonment of the Greenlandic settlements by the 15th century.

The Final Years and Disappearance of the Norse Settlers

By the late 14th and early 15th centuries, the Norse settlements in Greenland were in severe decline. Records indicate that the Western Settlement was abandoned first, followed by the Eastern Settlement.

The exact reasons for the settlers’ disappearance remain a topic of debate, but it is clear that a combination of environmental, economic, and social factors contributed to their demise.

The final years of the Norse in Greenland were marked by increasing isolation, as contact with Iceland and Norway dwindled.

The settlers faced mounting hardships, and by the early 15th century, the last remnants of the Norse Greenlanders had disappeared, leaving behind a rich archaeological legacy for future generations to uncover.

Archaeological and Historical Insights

Archaeological discoveries in Iceland and Greenland provide invaluable insights into the daily lives and societal structures of the Viking settlers.

These findings, combined with historical records and sagas, help us understand the complexity and adaptability of Norse culture.

Key Archaeological Sites in Iceland

Several key archaeological sites in Iceland provide valuable insights into the early Viking settlements.

The ruins of longhouses in Reykjavik, the remains of Viking Age farmsteads in Skagafjörður, and other sites across the island reveal the Norse settlers’ way of life.

These excavations have uncovered tools, household items, and structures that illustrate how the Vikings adapted to their new environment.

These findings also highlight the settlers’ reliance on livestock farming, their use of local materials for building, and their interactions with the natural landscape.

The archaeological record in Iceland continues to shed light on the complexities of Viking society and their impressive ability to thrive in a challenging environment.

Key Archaeological Sites in Greenland

In Greenland, significant archaeological sites include the Eastern Settlement at Qassiarsuk, the Western Settlement near Nuuk, and the bishop’s seat at Gardar.

These sites have provided a wealth of information about the Norse way of life, including their farming practices, trade networks, and religious activities.

Excavations at these sites have uncovered artifacts such as tools, weapons, and religious items, as well as the remains of buildings and farms.

These discoveries help to paint a detailed picture of the Norse settlers’ daily lives and their interactions with the harsh Greenlandic environment.

Artifacts and Their Significance

The artifacts uncovered at both Icelandic and Greenlandic sites are crucial for understanding the Viking Age.

Items such as tools, pottery, jewelry, and everyday household objects provide insights into the technology, trade, and cultural practices of the Norse settlers.

For example, the discovery of walrus ivory in Greenland indicates the importance of this commodity in trade with Europe.

Similarly, the remains of imported goods in Iceland, such as timber and metalwork, highlight the extensive trade networks that connected these remote settlements to the wider Viking world.

Insights from Sagas and Historical Records

Norse sagas and historical records offer a narrative complement to the archaeological findings.

Texts like the Landnámabók and the Icelandic sagas provide detailed accounts of the settlers’ journeys, their conflicts, and their daily lives.

These literary sources, while sometimes mythologized, offer valuable context and enhance our understanding of the Viking Age.

Historical records also document significant events, such as the conversion to Christianity and the interactions with indigenous peoples in Greenland.

By combining archaeological evidence with these written sources, historians can build a more comprehensive picture of the Viking settlements in Iceland and Greenland.

Conclusion

The legacy of the Vikings in Iceland and Greenland is a testament to their remarkable adaptability and resilience.

By examining the archaeological and historical evidence, we gain a deeper appreciation for the Viking Age and the enduring impact of Norse settlements in the North Atlantic.

Summary of the Viking Legacy in Iceland and Greenland

The Viking connections to Iceland and Greenland represent remarkable chapters in the broader story of Norse exploration and settlement.

The Norse settlers’ adaptability, resilience, and ingenuity allowed them to thrive in some of the most challenging environments in the North Atlantic.

Their legacy is evident in the archaeological sites, artifacts, and historical records that continue to reveal new insights into their way of life.

From the establishment of the Althing in Iceland to the innovative farming practices in Greenland, the Norse settlers left an indelible mark on these regions.

Impact on Modern Understanding of the Viking Age

Modern research and archaeological discoveries have significantly enhanced our understanding of the Viking Age and the Norse settlements in Iceland and Greenland.

These findings challenge earlier assumptions and provide a more nuanced view of the Norse people’s achievements and struggles.

The study of these settlements also highlights the importance of interdisciplinary research, combining archaeology, history, and environmental science to uncover the complex dynamics of Norse society.

This ongoing research continues to shed light on the Viking Age, offering valuable lessons about human resilience and adaptation.